Reviving Rohingya language: Nastaliq calligraphy finds new life in refugee camps

- Ahtaram Shin

- Nov 30, 2024

- 3 min read

By Anuwar Sadek, 30, November 2024

For decades, the Rohingya language was erased, forbidden to flourish in its own homeland. Yet, many Rohingya have refused to let it vanish. Among them is Husain Ahmad Siddiqi (Naisafuru), a quiet revolutionary whose struggle is to restore his people's language and identity. Now, in the heart of a refugee camp, he is waging a relentless battle to preserve and teach the language that defines his people, turning his dream into reality—against all odds.

"Since 2012, I have passionately dedicated myself to learning and teaching our language in Myanmar, even though it was forbidden. I had to do it secretly with a team, but despite the challenges, our team succeeded in teaching many students. Today, some of them are educators themselves and have become masters of the language," Husain shared.

Myanmar is home to diverse ethnic groups, including the Rohingya, who are rich in language, culture, traditions, and history. However, since the era of General Ne Win’s administration, systemic racial discrimination has stripped the Rohingya of basic rights. Denials of citizenship, freedom of movement, education, healthcare, and religious and cultural freedoms have left their community marginalized and oppressed.

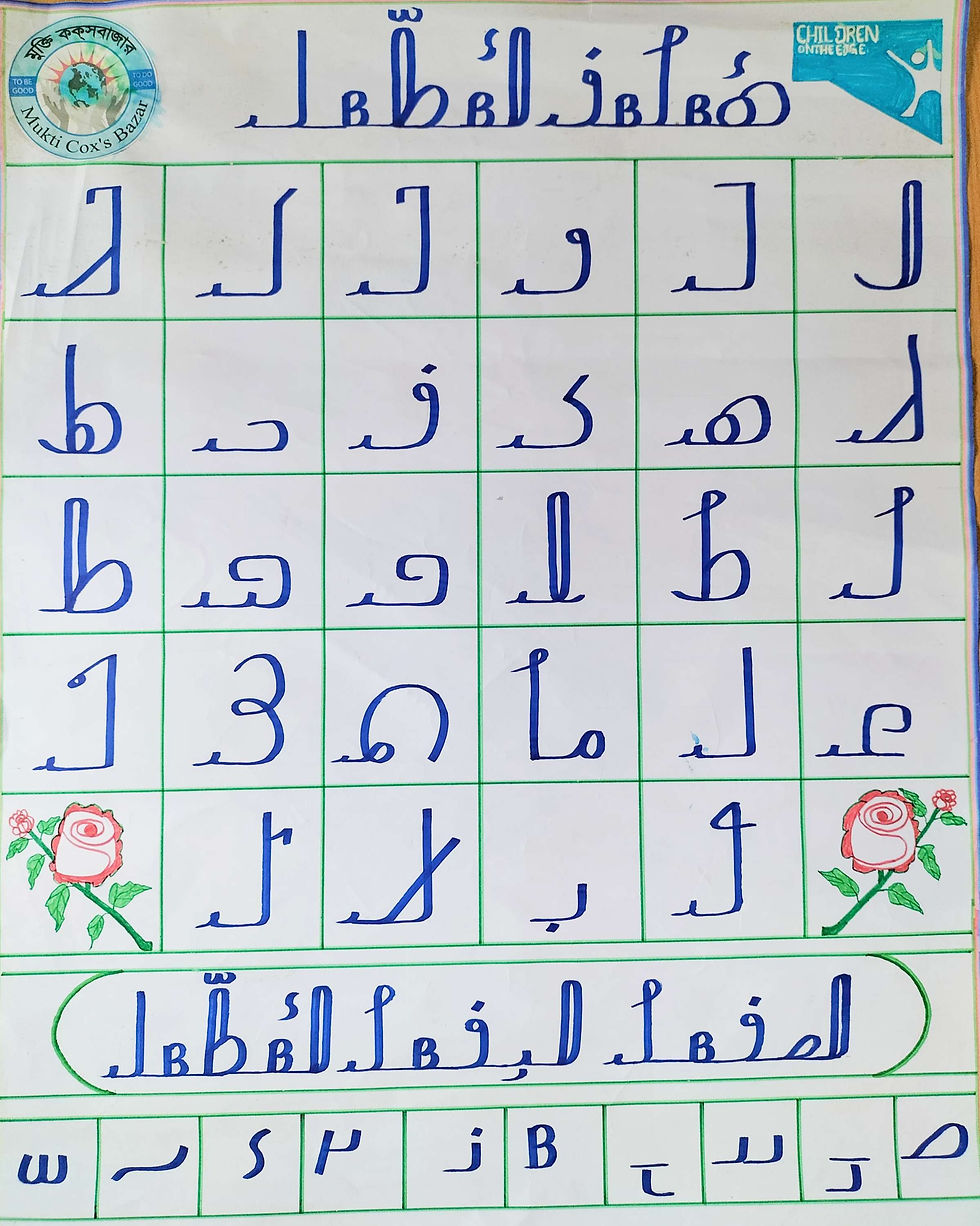

The Rohingya have a long linguistic heritage, tracing back to the use of Nastaliq calligraphy in earlier times. In 1980, Moulana Hanif, a renowned Arabic scholar and professor at the Arabic University in Nila, developed 28 Rohingya alphabets inspired by Sanskrit and Nagarik Language. Collecting from the Stone of Arakan State, Myanmar Museum, London Museum, inscriptions and documents, Moulana Hanif created a foundation for Rohingya literacy. To honor his contribution, the script was named the Hanifi Script after him.

Despite the existence of a well-developed language, writing scripts, and textbooks, the teaching and use of the Rohingya language were banned in Myanmar for decades, silencing a critical part of their identity.

After fleeing to Bangladesh, the Rohingya finally escaped the oppressive restrictions on their language. They began teaching the Hanifi script through WhatsApp groups for the elderly and in Moktabs—Islamic primary schools—for young children. Husain has been at the forefront of this effort, tirelessly working to promote the widespread use of the Rohingya language and ensure it is taught freely across the refugee camps.

"We are ordinary refugees like others; people do not pay much attention to us. Yet, despite everything, one-third of our community here is learning the language," Husain added.

Hussein team has collaborated with Mohammed Noor from the Rohingya Language Council. Noor, the founder of R-Vision, has initiated efforts to transcribe Rohingya subtitles for R-Vision’s daily news. Additionally, they partnered with John Littleton, a donor from Mukti Cox’s Bazar, to implement the Hanifi script in all camp-based learning centers, pending permission from the Rohingya Relief and Refugee Commissioner (RRRC).

"If we can read and write in our language, we can easily document our own history, learn other languages, and study chemistry and mathematics," agreed Mohammed Tofiq.

Currently, there are 400–500 students who can now decode the script without difficulty. "When we teach Hanifi, we don't need to translate the meanings like we do with Burmese and English. It also helps to understand Burmese words and reduces the time needed for explanations,” Tofiq explained.

The Hanifi script is easy for the Rohingya to grasp because of its similarity to the Arabic alphabet, which they practice in primary 'Moktabs'. "I have completely finished the basic textbook 'Rohingya Kaida' at the Mukti Cox’s Bazar learning center. Now I can write and read it, filling my heart with happiness. There are also some funny words included in that book, which make me smile while studying in the classroom or at home," a student expressed.

Having the freedom to restart learning their own language has brought overwhelming joy and a new life of Rohingya language for the Rohingya refugees. However, many teachers and parents worry about the uncertainty of formal permission to continue collaborating with the learning centers and having very rare support from education sector for it. The hope remains that these efforts will be formally recognized, ensuring the Rohingya language thrives once again.

--

Edited by Ahtaram Shin